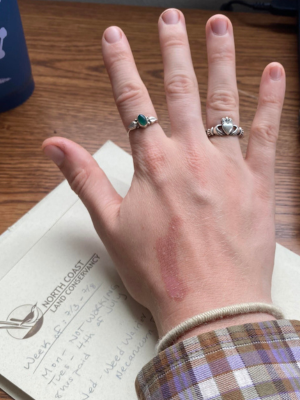

Callista works pulling knotweed at NCLC’s Necanicum Forest Habitat Reserve.

By Callista Martin

NCLC Stewardship Intern

In the space of a few hours at North Coast Land Conservancy’s Necanicum Forest Habitat Reserve, many attacks occurred.

First, there was me (and our volunteers) attacking knotweed with incredible vigor. Then, there were the blackberry thorns attacking me even through the thick denim of my jeans. I would later come to find out as I undressed for the shower that a tick had spent all day attacking my left thigh, ’til I tugged her free. Finally, there occurred two simultaneous attacks: Me, rushing past a cow parsnip in my haste to find more knotweed; The cow parsnip, stem broken open by my carelessness, attacking my dangling hand.

Such an unassuming name, cow parsnip. When you pass them in the forest, they look like a friendly fellow, with their large hairy leaves, thick stems, and clusters of small white flowers that resemble a bowl overflowing with popcorn when in bloom. Cow parsnip’s Latin name, Heracleum maximum, sounds much more foreboding as it invokes the mythological hero, and this perhaps is a more accurate representation of the powers the plant possesses. The colloquial name “Satan celery” also does some of the legwork in conveying danger.

The good news is that if you are kind to it, cow parsnip will be kind to you. Brush past it, step around it, feel the soft leaves with your fingertips. The cow parsnip welcomes gentle handling. It is only when force is applied and the stems are broken open that the wrath of Satan celery comes to pass.

Inside the stem is a thick, clear and poisonous sap. Once this sap touches the skin, you enter the danger zone—yet the cow parsnip offers you one last chance to avoid the blistering and burning rash it can produce. It needs its trusty sidekick in skin damage: the sun. Without exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light, the sap can be harmlessly washed off, and you may go on your merry way, frolicking through the undergrowth. But if you are like me and neglect to catch your mistake in time, or perhaps notice it but fail to take the warnings of your elders seriously, or maybe even leave the sap there purposefully as a personal science experiment, prepare for an unpleasant experience. I underestimated just who I was dealing with.

First, let’s talk about skin. What is the cow parsnip sap up against? The human body is made up of many different kinds of cells, each with a different job that helps keep your physical form up and running. Epithelial cells are one such category, and these cells form your skin. Epithelial cells pack tightly together like a carefully constructed brick wall, and their job is similar to that of a brick wall as well: to keep the big bad wolf from blowing the house down. Or, in other words, to act as a protective layer to prevent unfriendlies (microbes, viruses, bacteria) from sneaking in and wreaking havoc on your vulnerable insides.

First, let’s talk about skin. What is the cow parsnip sap up against? The human body is made up of many different kinds of cells, each with a different job that helps keep your physical form up and running. Epithelial cells are one such category, and these cells form your skin. Epithelial cells pack tightly together like a carefully constructed brick wall, and their job is similar to that of a brick wall as well: to keep the big bad wolf from blowing the house down. Or, in other words, to act as a protective layer to prevent unfriendlies (microbes, viruses, bacteria) from sneaking in and wreaking havoc on your vulnerable insides.

So how does the cow parsnip go about breaking down the epithelial brick wall of defense that is our skin? Furanocoumarins. These are the chemical compounds produced by Satan celery that cause damage, but we can refer to them as FUs for both convenience and amusement. You may actually be aware of FUs without realizing it—they are responsible for the warning on many prescription medications cautioning against the consumption of grapefruit. Fellow Zoloft users, be warned!

The FU variation found in grapefruit causes issues in the gut and liver, changing the way certain medications are broken down by the body. In the case of Zoloft, for example, FUs limit the amount of SSRIs entering the bloodstream, meaning you are actually receiving a lower dose of the medication than intended. Doctors prescribe a certain dose for a reason—keep this in mind before undoing their efforts downing bottomless greyhounds at brunch.

Shockingly, FUs were not invented by deviously scheming grapefruits to mess around with our medicines. It turns out that grapefruit and cow parsnip (along with many other related plant species) developed furanocoumarins as an important part of the immune system team, protecting them against attackers big and small: from hungry elk, to disease-causing microorganisms. When the plant is physically wounded or being invaded by pathogens, it responds by increasing production of FUs, sending them forth to warn the assailant to get lost. Cow parsnip believes in an eye for an eye and a tit for a tat. So when I snapped the stem of one of these reasonably revengeful plants, it was only fair that I received a wound in kind.

Now that we’ve been introduced to both fighters in the ring, the match can begin: sap vs. skin, FU vs. epithelial cell. The referee who begins the match is, in this case, the sun—or more specifically, UV-A radiation. The ultraviolet (UV) light that the sun sends down to earth comes in two forms: A and B. UV-B makes up only a small portion of the rays that reach through the atmosphere, and while it is the main cause of sunburn and skin cancer it does not penetrate very deeply into the skin. UV-A is much more common and reaches all the way through the epidermis, the culprit of wrinkles, skin aging, and tanning. While both UV-B and UV-A can cause serious damage, it is the latter that activates cow parsnip sap and its FU’s. The two contestants sit on opposite sides of the ring, eyeing each other menacingly but remaining peaceful, until the UV-A ref enters and signals them to start throwing punches.

Unfortunately for our poor epidermis cell, it is a fairly one-sided match in favor of the furanocoumarin. Once the sun’s UV-A rays enter the picture, the FU springs into action, smartly taking aim at the most vulnerable part of the epithelial cell: the nucleus. Like a boxer aiming for the head to KO their opponent, a good hit to the nucleus will similarly take away the cell’s ability to perform. This is because inside the nucleus, the head of the cell, is the DNA, the brains of the cell. These intricately woven strands of genetic material are what direct cellular functioning. Just as an injury to the brain can be fatal to us, so too can an injury to the DNA be deadly for a cell.

When the FU enters the epithelial cell, it can slip through into the nucleus and access the DNA. Aided by UV-A rays, the FU is able to form a bond with the DNA, latching onto it. While this may not seem like a big deal, the health of the cell is dependent on the ability of the DNA to be read and copied by other molecules. With the FU linked on to the DNA, it cannot be copied accurately, like trying to read a recipe that has been stained by a clumsy hand and a coffee mug full to the brim. The words become blurred and distorted, and ultimately unreadable. When the DNA copying process, called transcription, is halted, all hope is lost for our vulnerable epithelial cell. Admitting defeat, the cell triggers apoptosis—programmed cell death—the self-destruct button of the cell. The fight is over. The furanocoumarin reigns supreme.

When my hand made contact with the broken stem, millions of FU’s from the cow parsnip’s sap were spread across millions of my epidermal cells. In each one, the FU’s followed the same routine: 1) enter the nucleus, 2) bind to the DNA when triggered by UV-A rays, 3) halt transcription, and 4) trigger apoptosis. However, none of this was visible to my naked eye. Instead, what I saw is the result of those dead and dying cells: the burn, AKA phytophotodermatitis. Phyto, plant; photo, light; derma, skin; itis, inflammation. If the word were a math equation, it would read plant + light = skin inflammation. An accurate summary of events, I’d say, as I watched my skin bubble and redden over the next few days.

The mark is fading now. My own robust immune system is generating new epithelial cells in the aftermath of the attack, rubble rebuilt once again. An incredible four weeks have passed since I foolishly made contact with the sap of the cow parsnip, and I will likely carry the scar with me for months to years. Whenever I glance down, I will be reminded of the lessons learned that day. First, listen to your elders (and take them seriously). Second, don’t treat your body like a science experiment unless you are prepared to get burned (literally). Finally, forgive the plants but never forget: be gentle with them or they might bite back.

Comments