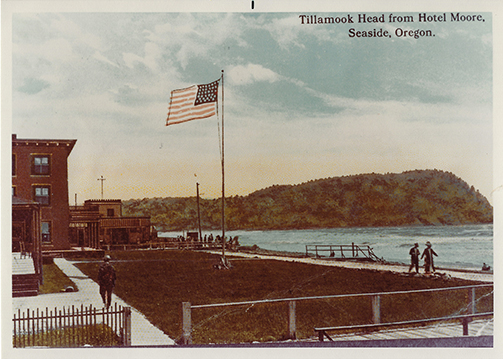

Photo courtesy of Seaside Museum & Historical Society

For thousands of years, the trees blanketing Tillamook Head grew to maturity, with wind and fire creating the only gaps in an otherwise unbroken rainforest canopy. The First Peoples of this coast harvested Sitka spruce roots to weave into baskets, rain hats, and ropes for whaling; the western redcedars they selected for use as canoes or for house construction would have been the most accessible trees, close to the shoreline. When white settlers opened the first holiday hotels in Seaside in the late 1800s, the headland guests gazed at, photographed, and sketched had been essentially the same for millennia.

In 1918 the U.S Army Spruce Division began selective cutting of Sitka spruce on Tillamook Head; the wood was used to build strong, lightweight airplane fuselages for use in World War I. Industrial-scale clear-cut logging on Tillamook Head followed.

The first steps to conserve forestland on Tillamook Head were taken in 1932, when fledgling Oregon State Parks acquired a tract of land that would grow to become Ecola State Park. The park area later expanded, as the state acquired more adjacent lands. The Feldenheimer family’s gifts of forest land next to Ecola State Park beginning in 1977 further expanded Oregon State Parks’ footprint on Tillamook Head. With North Coast Land Conservancy’s acquisition of the Boneyard Ridge property in 2016 and a second private conservation owner’s purchase of 340 acres next to the park that same year, about half of the forest on Tillamook Head is now on a trajectory to once again becoming a mature coastal rainforest.

RE-WILDING TILLAMOOK HEAD

How do you re-wild lands that have functioned as a tree farm for nearly a century? It’s the key question stewardship staff at North Coast Land Conservancy are grappling with as they begin restoration of Boneyard Ridge, high on Tillamook Head. And we’re not alone. Other conservation landowners around the mouth of the Columbia River—and around the country—are facing the same challenge.

Parts of Boneyard Ridge can effectively be left alone to grow into what scientists call “late seral forest.” Such old-growth forests have large, old trees in a variety of species. They also have gaps in the forest with younger trees and shrubs. They have large snags and downed wood on the forest floor as well as woody debris in the streams. The oldest stands of trees on Boneyard Ridge are about 50 years old. They currently have about the right density of tree, and as they grow, storm winds will do natural thinning. The youngest stands, where trees are as little as two years old, are much too dense and will need to be thinned. Stewardship staff is still weighing the best way to do that. Left alone, the young trees will all grow tall and skinny, allowing little light to reach the forest floor. Eventually a winter windstorm will likely blow down the even-aged stand of trees before they have the time to grow into the big, old forest we want to encourage. NCLC may accelerate the thinning process with helicopter logging, as Oregon State Parks is doing in adjacent Elmer Feldenheimer State Natural Area.

The science on which these restoration efforts are being based is new and still evolving. As we work to create rainforest conditions throughout the coastal-fronting forests in the area we call the Coastal Edge—on Tillamook Head and, one day, in the proposed Rainforest Reserve to the south—we will be contributing to that science.

Comments